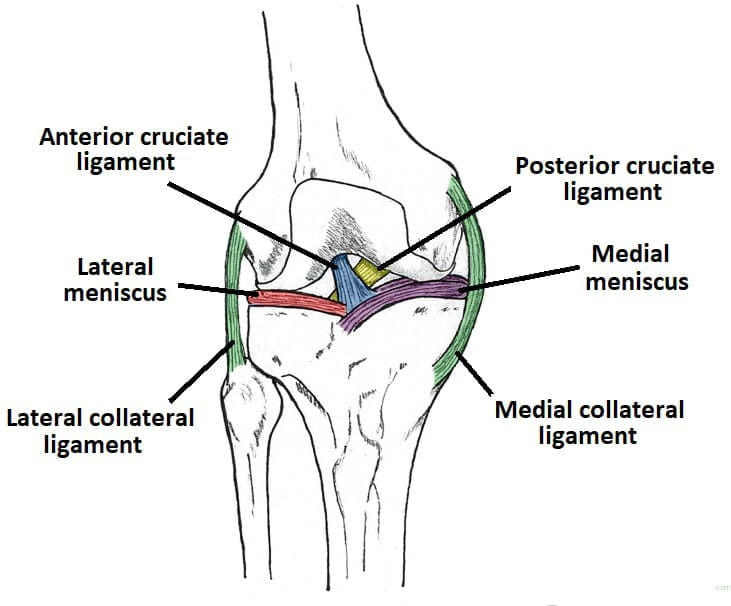

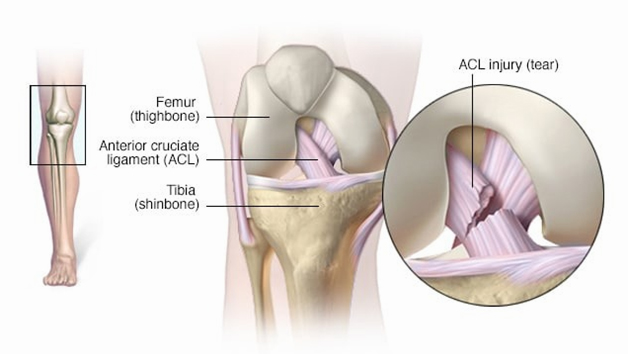

The knee is a complex joint. In a simple sense, it acts like a hinge. The femur (thigh bone), meets up with the upper portion of the tibia (shin bone). The patella (kneecap), sits in front of these two bones. The end of the femur and the upper portion of the tibia are coated with cartilage to allow the joint to move smoothly. There are several structures around the knee joint, called ligaments that connect one bone to another, making the knee stable. Ligaments are like strong ropes, keeping the knee stable. The collateral ligaments are on the sides of the knee. The medial (MCL) and lateral collateral ligaments (LCL ) prevent the knee from bending in a sideways fashion. The other two major ligaments in the knee are the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).

The ACL prevents the tibia from sliding forward with respect to the femur. It also helps provide rotational stability to the knee. Without the ACL, the tibia has a tendency to “spin” or rotate abnormally with respect to the femur. After the anterior cruciate ligament is torn, walking and running in a straight line may be well tolerated. However, cutting, pivoting and twisting activities are very difficult to perform in an ACL deficient knee, as the knee has a tendency to “pivot” out of place, or “give way” which is problematic for multiple reasons

Knee injuries are very common in sports, the workplace and at home. One of the most common knee injuries is a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL. The incidence of injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament is estimated at 200,000 injuries per year.

Hyperextension of the knee

Sudden change in direction

Stopping suddenly

Deceleration while running

Landing awkwardly from a jump

Direct collisions

Football, basketball, skiing, wrestling and soccer are considered high risk activities for ACL injuries. Approximately 70% of ACL injuries occur through non-contact mechanisms. Often, the injured person describes landing awkwardly on the involved knee and recalls having a sensation that the knee went in one direction while the body went in another

As people experience these “giving way” events, they lose trust in their knee, making it very difficult to participate in sports that involve cutting, pivoting and twisting or sudden change in speed and direction. Some people even have “giving way” events with usual, daily activities. ACL tears that are left untreated often lead to injury to the cartilage of the knee. With a torn ACL, the knee is at risk for “giving way” episodes.

During one of these episodes, the knee pivots and the smooth cartilage surfaces sheer against one another, which can cause damage to the cartilage or cause the meniscus to tear. Damage to the meniscus and smooth cartilage predisposes the knee to developing arthritis. Each “giving way” event puts the knee at further risk for damage.

The two most useful tools used to make a diagnosis of an ACL tear are:

• The patient’s recollection of the injury, and

• A good physical

It is common for one to hear and/or feel a “pop” when the ACL tears. The injury is usually followed by swelling and pain. If the swelling is significant, it can limit the normal range of motion of the knee. Often, aspirating, or draining, the knee of the excess blood can be helpful to relieve pain and help regain range of motion.

An MRI scan is also a very useful tool, as the scan can help confirm the diagnosis of injuries to meniscus, cartilage and other structures in the knee

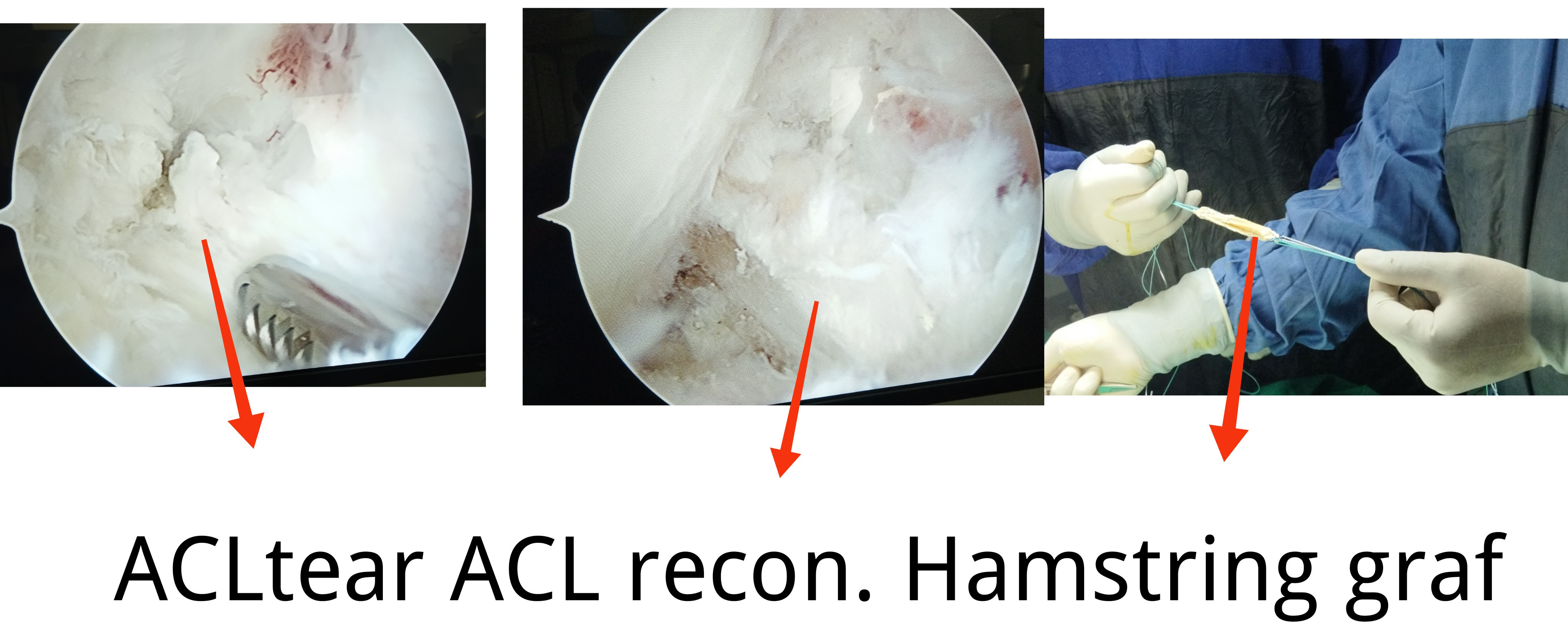

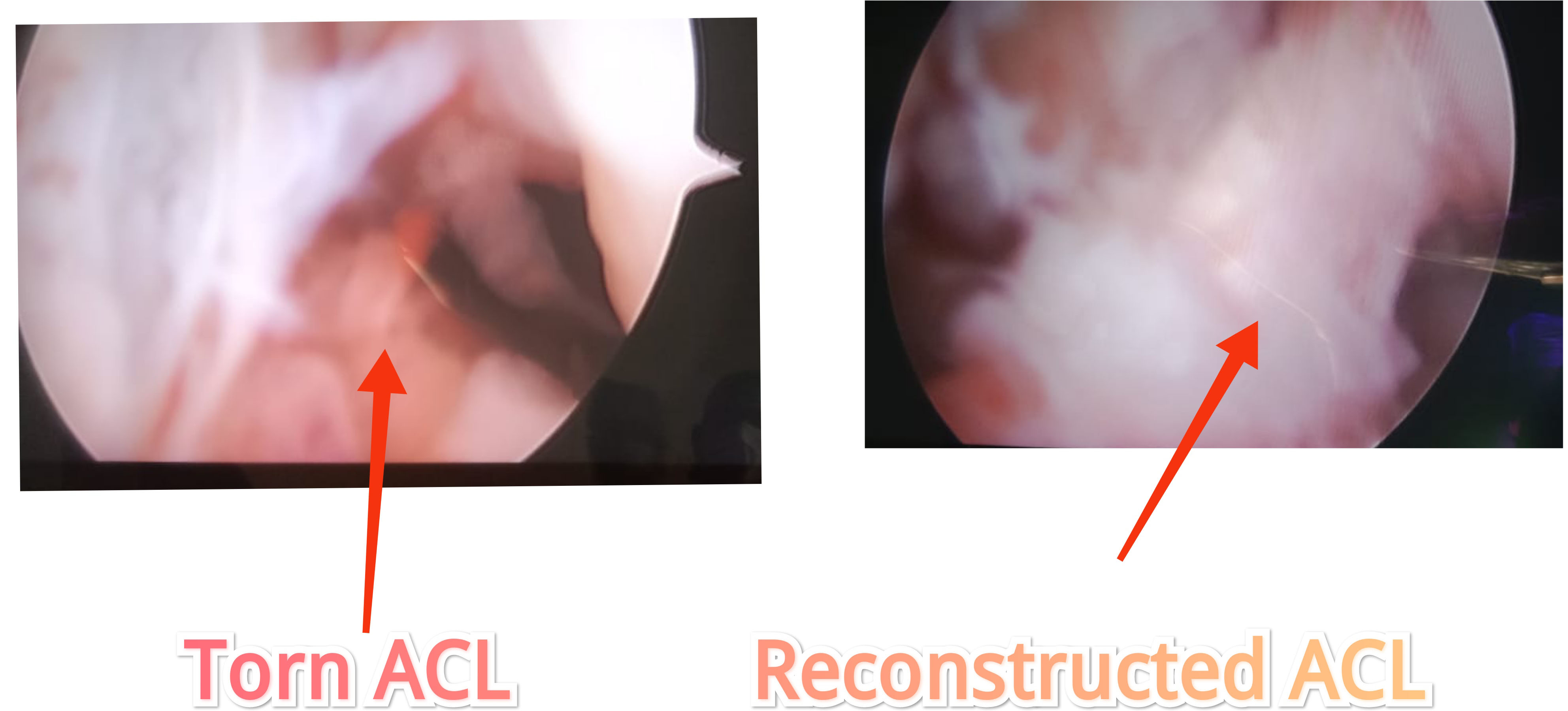

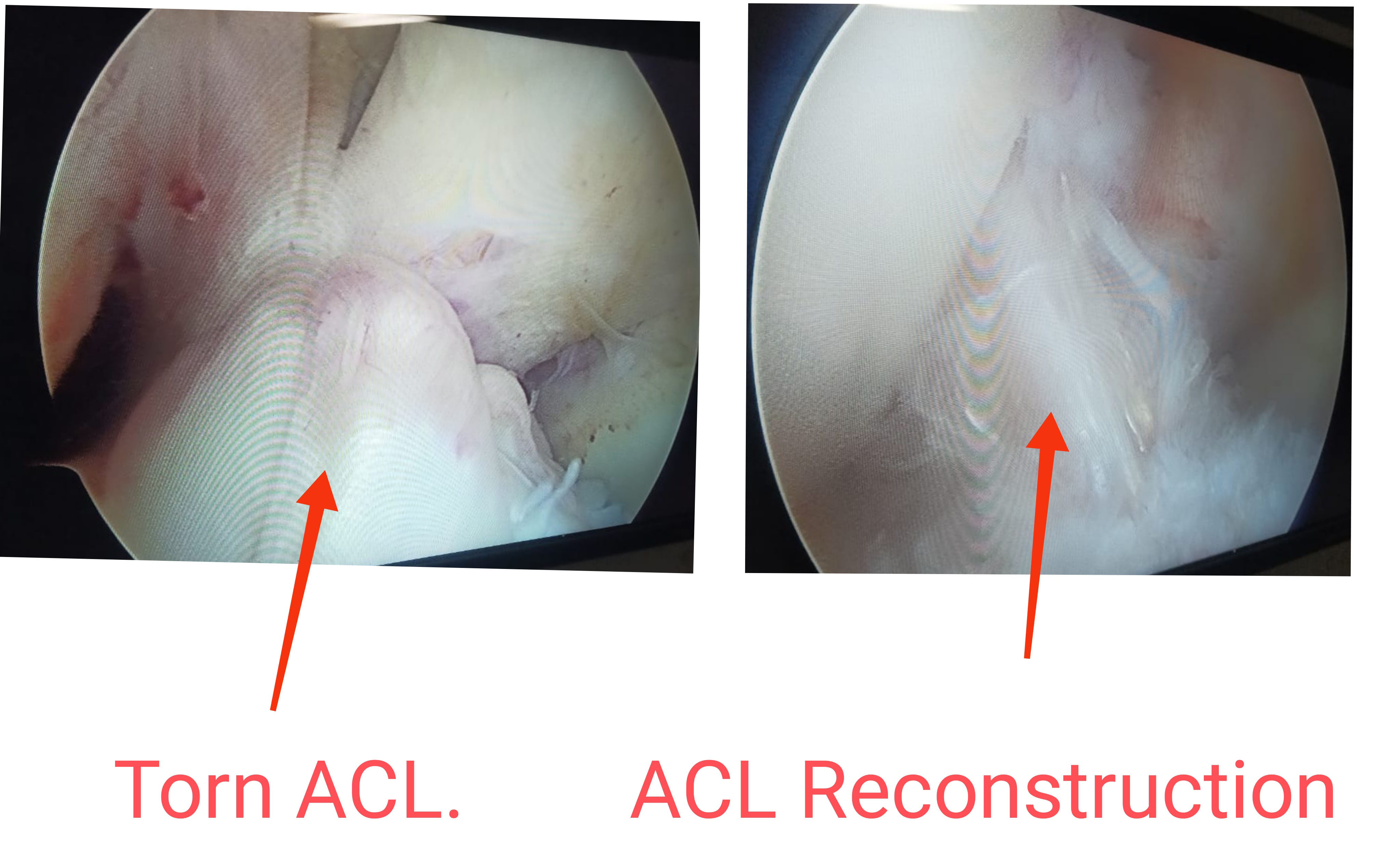

The goal of surgical treatment of ACL tears is to restore stability and function of the knee. In an ACL reconstruction, a “graft” is used to rebuild the torn ligament. The graft used to reconstruct the ACL can be one’s own tissue (autograft). The most commonly used autograft tissues are taken from either the patellar tendon or the hamstring tendons. The procedure is done with an arthroscope through several small incisions.

This “scope” contains optic fibers that transmit an image of your knee through a small camera to a television monitor. At this time, other possible problems, such as meniscal tears or cartilage damage, can be addressed. During the procedure, surgeon will drill a small tunnel through the femur and the tibia. The graft is fed into bone tunnels and held in place with a fixation device.

Website Designed By: Quick n Host